NOTE: This is an original research article. To date I am unaware of a study that has been done regarding metal pens spanning Late Antiquity through the Middle Ages to the Renaissance and Early Modernity. If you have any information about studies or papers on this subject please let me know!

“There were no metal pens pre-17th century,” is the common wisdom one hears. After all why waste such a precious substance as metal on a mere writing instrument. Well, that shows you the thinking of the twenty first century person, not the thinking of the pre-17th century person. I was doing some research several years ago on ink wells and ran across something that blew this pre-conception out of the water. A month ago I was doing some follow-up research and ran across something that made my jaw drop. Metal nibs were not only made and used pre-17th century but entire pens were made from metal and it goes back to at least the roman era of England and Germany.

This blog entry focuses on metal writing pens pre-17th century. Metal lining pens seem to have been in use for very long periods of time as well. Please visit Alexandre Saint Pierre’s blog for information on lining pens. He has done excellent work already and will be doing follow-up work as life allows him to.

Several years again I ran into an article about a set of 11 nibs being found in Hungary. The article started off with:

“We found an incredibly interesting and one of its kind set of 11 bronze pen nibs, which used to be put on the pens during the Golden Age of Simeon I of Bulgaria,” archaeologist Professor Nikolay Ovcharov announced

For obvious reasons this grabbed my attention. I have searched high and low for pictures of these pens. Simeon I of Bulgaria ruled over Bulgaria from 893 to 927. The article also said:

“Each of these pen nibs, which are cone-shaped, has different diameter, which means that they were supposed to make different lines of ink – wider, smaller and so on,”

Wait a minute. You’re telling me that not only metal nibs exist pre-17th century, but different sized metal nibs came in sets much like they do today? Okay, yes, but it says “one of a kind.” Still all my preconceptions about metal nibs are gone and this area of knowledge deserves some research.

Since then I would sporadically do research but kept coming up empty. I wasn’t looking in the right places it turns out. I learned to search museum websites and other archaeology artifact sites from Mistress Aelfwyn Hatheort in Ealdormere And suddenly I found several versions of metal nibs and to my utter surprise entire pens made of metal. She found many on her own and put them on her Pinterest account and shared the links with me. It is because of her I was able to succeed at doing more research on these tools.

Here is the South Hampton’s Archaeology Object Database example of a medieval metal nib made from a copper alloy.

Here is a set of copper alloy pen nibs thought to be from between 1500 and 1600. They have an “X” shaped insert at the nib base, opposite the pen tip.

Okay so we have copper alloy pen nibs from late 9th all the way to the end of the 17th century and in disparate places of Europe. Very obviously this was not a single incident and it was not just in one place. Metal pen nibs pre-17th century did exist as more than just a one time incident. That metal has always been a copper alloy of some kind or another for all of these surviving nibs. Not steel like most modern calligraphy pens.

Then I ran across this gem of a find in the Museum of London. I was looking for more metal nibs and instead found item number 82.145/2 an entire pen made of metal. As the description say it is a “Copper alloy pen with a split nib” It is from the medieval time period.

My jaw dropped.

Then I found another copper alloy pen from the medieval time period in the Museum of London’s database.

These are also pre-17th century. Each is about 11 cm (4.33 inches) long. In comparison to the modern pen holder dip pens this is rather short. But they are what they are.

They also have a bone pen from the 12th to 13th century. I didn’t think about a bone pen either, but it makes sense that bone could have and would have been used.

I looked into the British museum data base and found another metal split nib pen. It is part of a set of metal scribal tools and an ink holder. From romano-british times which ended in the 5th century. Moving the date of metal pens up to at least the 5th century and potentially to the first century A.D. And if the Romans had them in England, they likely had them throughout the Empire all the way across Roman Europe to the Italian Peninsula and across the northern coast of Africa. That of course is only a working hypothesis. But it is a reasonable one.

The conclusion is inescapable copper alloy pens and pen nibs have been used in Europe by scribes from potentially the first century AD all the way through the end of the 16th century and beyond.

But that’s not all.

When I shared the finds from the London Museum online something truly wonderful happened. Metal workers who saw the posts volunteered to make reproductions of them and then they gave them a select few people to test out including me. In less than two weeks I had three reproduction copper alloy pens in my possession to write with and comment on.

The pens came from Master Aethelstan Aethelmearson, OL of Ansteorra and The Honorable Lord Gerald Loosehelm of Northshield. And are pretty awesome.

The first pen was used by the Firestorm Ink Guild on a day I was sick and could not attend. It was used on a flat level surface, using iron gall ink and as reported to me it worked but had some ink flow problems. Typically speaking we see paintings of scribes using a sloped desk. And we can see from this picture flat and sloped make a real difference.

On the left is the writing of one of the reproduction pens on a level surface. On the right is the same pen on a 45 degree slanted surface.

In the mean time another pen was made and I received Gerald’s pen in the mail. The next week I showed up with my slanted scribal table and met Aethelstan at the Guild. I used iron gall ink and played some with it. The pens all worked to varying degrees of success. I was able to bring them home take pictures and do more writing tests. These pens are prototypes to work out any issues that may be present from making them for the first time. These are meant to be the first step toward getting a working reproduction tool to scribes.

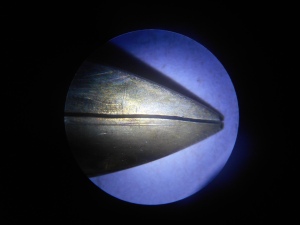

Aethelstan’s pen most resembles this pen from the London Museum.

It has a “scoop” on the opposite end from the nib.

As you can see from the picture is is a few millimeters wide. What could it possibly be used for? A lot of discussion was had regarding this subject on various discussion groups that saw the picture from the museum. Small scoop for pigments? Ingredients? Ear Wax Scoop? Now that last one may seem a bit far fetched to some but we know that ear wax was part of some recipes for making glaire. Apparently it helps keep the bubbles down when you mull the pigments with the glaire. I can definitively tell you that indeed the scoop does work for this purpose.

A quick aside. Notice how I am holding the pen. I am not resting it on my middle finger, instead I am holding it with my middle finger and thumb and my index finger helps the pen “rest” at the second knuckle from the tip of the finger. This is how we see scribes holding pens in miniatures in medieval manuscripts. It is very different from how we hold ball point pens and pencils of today.

And how does it write? Pretty well.

Remember this tool is new to me as a scribe and is a prototype pen on top of that. Despite an the newness involved in every aspect, it is writing extremely well. Later uses of the pen were even crisper. The capillary is a bit wide as discussed below.

Gerald’s pen most resembles this pen from the London Museum.

Okay, they’re nice looking, but how well do the pens write? Actually pretty well. Each metal worker used the smallest bladed saw they could to put in the capillary for the nib. We don’t know how it was done historically but this seemed a good choice by the metal workers.

However to this scribe the capillary is just simply too large as it creates a superhighway for the ink to flow to the tip. What we need is more of a crack in the metal for the ink to seep its way down. More metal pen making is in the works and the metal workers will be trying to determine how to put in the capillary the best way. Maybe a chisel is best, maybe sawing is best and then hammering the sides together is best. I will leave them to their work for they are the metal workers and I am just a scribe.

Here are some up close pictures of Gerald’s Pen.

The quill pen is “sharpened” by putting a final cut on the tip at around 45 to 60 degrees depending on the scribe. That is some serious attention to detail for the metal work.

I asked and received permission to make modifications to the pen. As a scribe I modify my metal nibs often enough that I felt pretty confident that I could do so with Gerald’s pen without destroying it. Of course if I did, that was part of it being a prototype.

This modification makes the pen very much like a quill pen nib. The curve causes there to be less surface space for the ink to hang on to. This holds the ink further back in the pen and helps regulate the flow of ink to the tip of the nib. Writing with this after the modifications had less ink flow problems, but still some.

Talking with the metal workers I asked if these pens would ever get sold and if so, for how much apiece. I was told by one of them that the pens take about 1.5 to 2 hours to make and that a fair price for that kind of labor would be about $75. I have no idea what the final prices will be as familiarity brings about a faster process and a better quality writing instrument. These are again, prototypes of reproduction pens.

Nonetheless, I was sent about $225 worth of scribal tools to test out and report back on. I am being allowed to keep at least one of the pens for ongoing experimentation and personal use.

I can not express to you how wonderful this research experience has been. Without Mistress Aelfwyn Hatheort in Ealdormere‘s knowledge about different databases and her assistance finding pens this would have taken me much longer. I am very grateful about how the metal workers Master Aethelstan and THL Gerald spontaneously volunteered to make some pens and let me try them out. It has been truly wonderful in all ways and I greatly appreciate it.

Short version? Copper alloy full pens and nibs existed and were used in Europe and surrounding areas from at least 400 AD until 1600 AD and beyond.

Pingback: Winter 2022 Edition of Magick, Crafty Makes, and Me | Witchcrafted Life·

If you want to know more about Roman writing, there are two very good books I can recommend (both should be in any British university library): Ellen Swift: Roman Artefacts & Society (2017), which has a whole chapter on how writing styles changed by incremental changes in cutting the writing pen and adjusting the slope of the writing surface and Hella Eckhard’s Writing and power in the Roman world (2018)

Hi nice article. I’ve found 2 metal (copper-alloy) pens.

One was found on a monastery site which existed 1450-1550

And the other suprisingly in a 14th context.

This article helped me with the determination.

If you want I can sent you the photos.

Certainly. I’d love to see them. Where are you located and where were the pens located?

My contact information is in the “About this Blog” link.

Pingback: Pointed Metal Pen Nibs: Not As Old As You Think – An Itinerant Scribe·

Pingback: Metal Pen Was Found in Roman Times – Global Firsts and Facts·

Great article. I went to an exhibition at the V&A about 10 years ago and it contained a surprisingly modern Italian pen. It was 14th century, I believe. I was really surprised to see it because I had heard the same nonsense about “no metal pens pre-17th century.” I believe a photo was in the exhibition catalog, I can try and track it down if you want.

I am always interested in more information about metal nibs and pens pre-1600.

Thank you for the wonderful article. I also thought that metal nibs were 17th century inventions. I have been making quill and reed pens for some time and teaching that process to any who would listen to my elocution for that long 🙂 Master Cynwyl McDare showed me an image of the metal pen that you had and it was like being hit in the face with a shovel.

I have since attempted to make one, trying to maintain similar construction to a quill pen (multiple scallop profile and centered capilliary slit). I attempted to use a shear process to cut the slit. This met with limited success. The shearing process causes the metal to deform sufficiently to create a slightly oval slit.

I thought about the concept of using a very fine jeweler’s saw to cut the slit but then the concept of the slit being too wide comes into play. I am going to try that next but I will try using a small hammer to slightly deform the metal to close up the slit some by striking directly on top of the slit.

I’ve also found that the ink has to have considerably more gum arabic in it’s formulation to get it to stick properly to the metal. Too little and the ink simply beads up under the nib and leaves the pen all at once the instant it touches the paper.

Good luck! I will be following this blog and attempting my own fabrication.

Cheers! Robert l’Etourdi.

A shovel to the face is how it felt to me the first time.

I am told that etching the capillary creates success. Gum Arabic amounts in period ink recipes are higher than many think. Do a search on my blog for gum Arabic in ink. I wrote an article about it.

Pingback: Major Event In June – SCA 50 | scribescribbling·

We modern peoples often underestimate the ingenuity and ambition of our ancestors.

may want to add “ability” to that list. i mean, look at brunelleschi’s dome; which engineers say should have been impossible for their technological level. it makes me laugh at how the majority of modern man finds our ancestors inept because they lacked the technology we have today; as if they couldn’t do anything because they didn’t have it.

Pingback: Metal Pens pre-17th Century | scribescribbling·

Pingback: A Traveling Scribe’s Tools | scribescribbling·

I for one would be willing to pay that much for a reproduction medieval metal pen! Are any of the metal workers considering making more? 🙂

Yes, they are. One is even ready to start selling them. Please contact me privately for their contact information. IantheGreen01@gmail.com

I should be very interested to know the exact composition of the “copper alloy” pens. I don’t suppose the Museum offered so much detail, did it?

I too am very curious as to the exact composition or kind of copper alloy.

In one instance we are told that the copper alloy is bronze. Any description given that says “copper alloy” is the description the museum gave. There aren’t many copper alloys out there and bronze is most likely but no, we do not have any further knowledge of the composition of the copper alloy or what copper alloy it is.

Excellent work. Well done.

Thank you.