Experiments that provide data are always a success. However, they don’t always give you the results you want or the results you expect.

I have been experimenting making ink by using different ingredients. On December 27, I promised you pictures of the inks with which I have been experimenting.

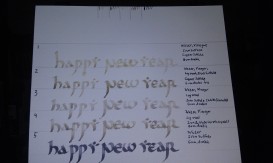

Drawing horizontal guide lines using a lead/tin stylus, I used 5 different C-1 nibs to write “Happy New Year,” in the Uncial script, each new sample ink getting its own nib. The thin black modern writing on the right side was done with a modern fiber pen. For your viewing pleasure:

Yes, these are all ferrous oak gall inks. Allow me to sum up the process I have detailed already; I boiled oak galls in water and and vinegar for inks 1-4. Where the notation reads “water, vinegar” it means oak gall extract boiled in water and vinegar. Boiling the oak galls extracts the tannic acid from the oak galls. Correctly stated (and in technical and potentially confusing jargon,) to the best of my ability, it would be:

Aqueous gallo-tannic acid solution with non-pasteurized vinegar.

The tannic acid reacts with iron of the iron sulfate and is supposed to turn black.

Number 5 is my control sample. The control sample is the standard – what everything else is being compared to – and, in this case, is known to be good ink. I should note that number 5’s ingredients list is not complete. It should read, “Water (including the tannic acid), Iron Sulfate, Gum Arabic, Egg Shells.” Egg shells are used to help balance the pH of the ink.

So what happened? Why isn’t all the ink black like #5?

The answer to that is what didn’t happen. The Iron Sulfate did NOT react well will the tannic acid in the solution. Something inhibited the reaction. It is interesting that when you look at the ink in the bottles they all look black, though obviously they are not. This could simply be because the brownish color is impeding light from going through the solution thus making it appear black. Though I believe this is only part of the answer. The rest of the answer, I believe, is that there was an incomplete reaction and so the black particles that are in the solution are also inhibiting light from going through by absorbing the light, instead of just blocking it like the brown particles are doing.

Returning to the ink on the page;

Notice the lines at the top of the page? Those are there as guides for looking at the ink after it dries under my 20X microscope. Under the microscope you can actually see the fine details of the ink. Sadly, I can’t take pictures of what my microscope sees, that kind of equipment is still prohibitively expensive to me.

Sample 1 – Very few black iron crystals form. In fact, almost none did. The ink in the bottle has a slight thin foam floating on it.

Sample 2 – You can actually see that the gum arabic has dried with fissures in it, either from cracking or having formed that way. However it is darker, has a few more iron crystals in it than sample 1 did and is a darker shade even without the iron crystals. The ink in the bottle had a strong foam layer about ¼” (4mm) thick. The writing in sample 2 has some “mottling” to it. This may have been caused by tiny bubbles trapped in the gum arabic.

Sample 3 – Looks very much like sample 2 but it has no fissures in it. There was no froth on top of the ink.

Sample 4- Has more iron crystals in it than sample 3 does.. There was no froth on top of the ink.

Sample 5 – Has abundant iron crystals in it. There was no froth on top of the ink.

So the question now is what has stopped the ink from turning black? Well, we can see a very marked difference in the coloration of the various inks. The fewer ingredients we have the darker the ink is. In samples 1-4 the Iron sulfate was the next to last ingredient to be added with gum arabic being the last ingredient. In sample 5 the ingredients were put in the order of: water, oak galls, drained the solution, added Iron sulfate to the solution, then egg shells and lastly gum arabic.

From this observation I strongly believe that the more ingredients you put in the more careful one needs to be about the order the ingredients are mixed in. It may be the other ingredients interacted so much with one another that there wasn’t anything left for the iron sulfate to turn black with.

So the next step I will be taking is to go back and look at the period recipes. I will be looking not only at the list of ingredients and amounts but also the order in which they were mixed.

There is another possibility I haven’t mentioned. And that is the simplest one of all. I didn’t extract very much tannic acid from the oak galls. Not enough tannic acid means a weak solution and thus a weak reaction and a thin and not very black ink. With the problem of ingredients needing to be put together in a specific order and this augments the problems that may be occurring.

Ah, more experiments to do and more ink to play with. This should be fun!

Pingback: Gold Mace – Chaos at the Castle AS 49 | scribescribbling·

Pingback: Soaking Ink Progress Report | scribescribbling·

Howdy! Someone in my Facebook group shared this site with us so I came to check it out. I’m definitely enjoying the information. I’m book-marking and will be tweeting this to my followers! Exceptional blog and amazing design.